A READING REPORT ON KANT'S PHENOMENA AND NOUMENA (March, 2013)

INTRODUCTION

In

the Kant’s ‘Critique of Pure Reason’, Kant’s classification of objects under

phenomena and noumena is probably one of the most misunderstood. Whether we

know something a priori at all (noumena) or a posteriori alone (phenomena),

Kant thinks that these two must work together and should not be so much

dichotomized. This reading report tends to bring to view, though summarily, the

stand of Kant on Phenomena and Noumena and how objects are divided according to

these.

EXPOSITION OF THE TEXT

Kant, in order

to cast our minds back to the previous stand thus: the interdependence of the

understanding and experience. He, here tries to reiterate that, although the

understanding can produce some pure concepts, these concepts never can go

beyond the empirical use (i.e. they are incapable of any transcendental

use. Writing in Kant’s words thus:

…everything which the

understanding draws from itself, without borrowing from experience, it

nevertheless possesses only for the behoof and use of experience.

A conception in

a fundamental proposition or principle has two uses thus: a transcendental use

when it is referred to things in general and considered as things in

themselves; and an empirical use, when it is referred mainly to phenomena (i.e.

objects of possible experience). The latter is more admissible because of the

two things necessary for every conception thus: the local form of a conception

(of thought) general; and the possibility of presenting to it an object to

which it may apply. Without the latter, it is, according to Kant, void, since

there is nothing to which it can be referred. Intuition it is, that attaches

objects to different conceptions and “all

conceptions, therefore”, according to Kant, “and with them all principles,

however high the degree of their a priori possibility, relate to empirical

intuitions…”

Consequently,

one cannot just relegate either of the phenomena and noumena to the background,

since both go hand-in-hand in such a way that the pure conception will remain

vague unless there comes a corresponding sensuous object to represent it to the

senses, and therefore, makes it more intelligible. For Kant, then, it follows

that the pure conception of understanding is incapable of any transcendental

use save for empirical use alone. This means that one cannot understand or know

anything (as it is in itself) which goes beyond the spatio-temporal world or

experience.

Phenomena

and Noumena, as both terms were used, refer to the ‘sensible’ and ‘the

intelligible’. It is Kant’s opinion also that ‘knowledge is necessarily

sensible for us, since he had claimed that cognition requires intuition which,

for us is sensible. Thought is the act of referring a given intuition to an

object. A pure category, supposedly devoid of all conditions of sensuous

intuition does not determine an object, but merely expresses the thought of an

object in general, according to different modes. This pure category is

incapable of establishing synthetic a priori principles which are, in fact, not

possible, since the principle of pure understanding are just nothing beyond

being empirical. In this case, any doctrine or law suggesting its use in the

transcendental sense is nothing but a mere illusion, as it can have a

transcendental meaning (which has less meaning than the pure sensuous forms,

space and time), but not a transcendental usage. He admits of a possible

illusion (pertaining the case of categories and transcendental usage) which

seems difficult to avoid, but dismissed it by stating that “they [categories]

are mere forms of thought , which contain only the logical faculty of uniting a

priori in consciousness , the manifold given in intuition”. Kant, nonetheless,

distinguishes between the inner, mind-dependent realm, and the outer, objective

mind-independent realm thus:

PHENOMENA AND NOUMENA

Kant

begins by noting that all that we perceive are nothing but representations and

appearances. He calls this realm of perception the realm of intuition, or

sensibility. The objects of perception (or intuition or sense) are called

phenomena. These phenomena, for Kant, are dependent on the mind, and thus he

writes, “they cannot exist in themselves, but only in us”. They are those

things that are possible for us to experience, and that we do experience,

because they are in agreement with our mental structure. This is not the case

with noumena.

Noumenon

is a posited object or event that is known (if at all) without the use of the

senses. For Kant, noumena may exist, but it is completely unknowable to humans.

They cannot be determined by categories

since the notion of noumenon is completely indeterminate. To think about

noumena then, Kant has two distinct ways thus: the positive sense and the

negative sense. A noumene in the positive sense would be a world of

understanding. According to Kant, if we understand it as an object of

non-sensuous intuition (an intellectual intuition), then it does not belong to

us as sentient beings. If this is the sense of noumena, then for Kant, it is

illegitimate (since intellectual intuition lies outside our cognitive power).

On the other hand, Kant writes that if we understand ‘noumenon’ as a thing so

far as it is not the object of our sensuous intuition, thus making abstraction

of our mode of intuiting it, then this is ‘noumenon’ in the negative sense.

This sense requires the cogitation of things in themselves. Since, for Kant, we

can only experience something within space and time, and if we could know the noumena, we would know

things as they are, but we know things only by appearances, i.e. as they

appear. “Hence what is called Noumena by us must be meant as such only in the

negative signification”, according to Kant. So he states that the division of

objects into phenomena and noumena is quite inadmissible in the positive sense

(even if conceptions admit of it).

CONCLUSION

Kant’s

point is not that there are objects and concepts unknowable to us or beyond the

phenomenal world. So even if Kant’s view is expressed thus: we know only phenomena but not noumena, it should be

understood as the claim that we know objects only as they appear to us (through

sensation), and not as they really are in themselves.

SPINOZA: GOD OR NATURE

INTRODUCTION

This paper is an attempt to examine Spinoza’s work on “Ethics”. His “Ethics” is an ambitious and multifaceted work which was fashioned after the geometrical method originated by Euclid; it is sub-divided into three parts. However, despite the great deal of metaphysics, physics, anthropology and psychology that make up Parts One (God or Nature), Part two (The Human Being) and Part three (Theological-Political Treaties) of his work, “Ethics”, Spinoza took the crucial message of the work to be ethical in nature. It consists in showing that our happiness and well-being lie not in a life enslaved to the passions and to the transitory goods we ordinarily pursue; nor in the related unreflective attachment to the superstitions that pass as religion, but rather in the life of reason. For clarity of work, this paper shall be dealing on only part one of Spinoza’s work, “Ethics”, that is, God or Nature (Deus, sive Natura)

This paper is an attempt to examine Spinoza’s work on “Ethics”. His “Ethics” is an ambitious and multifaceted work which was fashioned after the geometrical method originated by Euclid; it is sub-divided into three parts. However, despite the great deal of metaphysics, physics, anthropology and psychology that make up Parts One (God or Nature), Part two (The Human Being) and Part three (Theological-Political Treaties) of his work, “Ethics”, Spinoza took the crucial message of the work to be ethical in nature. It consists in showing that our happiness and well-being lie not in a life enslaved to the passions and to the transitory goods we ordinarily pursue; nor in the related unreflective attachment to the superstitions that pass as religion, but rather in the life of reason. For clarity of work, this paper shall be dealing on only part one of Spinoza’s work, “Ethics”, that is, God or Nature (Deus, sive Natura)

THE PHILOSOPHER, BARUCH SPINOZA

Baruch Spinoza, the noblest and most lovable of the great philosophers, as Bertrand Russell called him, was born in Amsterdam in 1632, of a family of Portuguese Marranos - Sephardic Jews who had been forcibly converted to Christianity by the Inquisition after his (Spinoza’s) expulsion from the synagogue. Spinoza is a rigid determinist, a relativist and arguably he is the greatest of all ethicists. His thought combines a commitment to Cartesian metaphysical and epistemological principles with elements from ancient Stoicism and medieval Jewish rationalism into a highly original system. His philosophy is so much influenced by the works of Descartes and Euclid geometrical method. Some of his works include: Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect – an essay on philosophical methods, Short Treatise on God, Man and His Well-Being – an initial but aborted effort to lay out his metaphysical, epistemological and moral views. He also wrote Descartes’ Principles of Philosophy, the only work he published under his own name in his lifetime, and then Ethics, his philosophical masterpiece. When Spinoza died in 1677, in The Hague, he was still at work on his Political Treatise; this was soon published by his friends along with his other unpublished writings, including a Compendium to Hebrew Grammar.

THE EXPOSITION OF HIS BASIC ETHICAL IDEAS ON PART 1

God or Nature (deus, sive natura): As accustomed to 17th century philosophers, Spinoza begins with definition of terms. The definitions of this Part One (God, or Nature) are, in effect, simply clear concepts that ground the rest of his system. He assert that, “By substance I understand what is in itself and is conceived through itself”; “By attribute I understand what the intellect perceives of a substance, as constituting its essence, and By God I understand a being absolutely infinite, that is, a substance consisting of an infinity of attributes, of which each one expresses an eternal and infinite essence.”[1] They are followed by a number of axioms that, he assumes, will be regarded as obvious and unproblematic by the philosophically informed. These include:

1. “Whatever is, is either in itself or in another”; 2. “From a given determinate cause the effect follows necessarily”.[2] From these, the first proposition necessarily follows, and every subsequent proposition can be demonstrated using only what precedes it.

In his propositions ranging from 1 through 15, Spinoza presents the basic elements of his picture of God. God is the infinite, necessarily existing (that is, uncaused), unique substance of the universe. There is only one substance in the universe. This substance is God and everything else that is, is in God. Hence he assumes that except God, no substance can be or be conceived. These assumptions proceeds in three simple steps; first, he establishes that no two substances can share an attribute or essence. Then, he proves that there is a substance with infinite attributes (God). It follows, in conclusion, that the existence of that infinite substance precludes the existence of any other substance. For if there were to be a second substance, it would have to possess some attribute or essence, but since God has all possible attributes, then the attribute to be possessed by this second substance would be one of the attributes already possessed by God. But it has already been established that no two substances can have the same attribute.[3] Therefore, there can be, besides God, no such second substance.

Furthermore, If God is the only substance (by axiom 1), and whatever is, is either a substance or in a substance, then everything else must be in God. “Whatever is, is in God, and nothing can be or be conceived without God”.[4] Those things that are “in” God (or, more precisely, in God's attributes) are what Spinoza calls modes.

Concerning nature, Spinoza insists, that there are two sides of Nature. First, there is the active, productive aspect of the universe—God and his attributes, from which all else follows. This is what Spinoza, employing the same terms he used in the Short Treatise, calls Natura naturans, “Naturing Nature”. Strictly speaking, this is identical with God. The other aspect of the universe is that which is produced and sustained by the active aspect, Natura naturata, “natured Nature”. By Natura naturata I understand whatever follows from the necessity of God's nature, or from any of God's attributes. In other words, all the modes of God's attributes insofar as they are considered as things that are in God, and can neither be nor be conceived without God.[5]

EVALUATION

What does it mean to say that God is substance and that everything else is “in” God? Is Spinoza saying that rocks, birds, mountains, rivers and human beings are all properties of God, and hence can be predicated of God (just as one would say that the table “is red”)? When a person feels pain, does it follow that the pain is ultimately just a property of God, and thus that God feels pain? Conundrums such as this may explain why there is a subtle but important shift in Spinoza's language, as of Proposition Sixteen. God is now described not so much as the underlying substance of all things, but as the universal, immanent and sustaining cause of all that exists: “From the necessity of the divine nature there must follow infinitely many things in infinitely many modes, (everything that can fall under an infinite intellect)”.[6]

The picture which Spinoza paints about God and Nature makes them look the same. However, I argue that Natura Naturans is the most God-like side of God, eternal, unchanging, and invisible, while Natura Naturata is the most Nature-like side of God, transient, changing, and visible.

On another note, Spinoza saying that God is the cause of all things will remove responsibility from humans. For if that is the case, no one should be blamed or praised his/her action(s), since God has caused them. “My thought, your thoughts and the thoughts of everyone in the world make up God’s thought[7]” he asserts. I think that at this point he is falling back to his deterministic view of life hence rendering repentance, responsibility and objectification of our life useless. And again, this point will be making God the cause of evil in the world since he is in everything.

For centuries, Spinoza has been regarded by some philosophers as a pantheist, while for others, he is not. However, I argue that he is not a pantheist because for him, God is to be identified only with substance and its attributes, the most universal, active causal principles of Nature, and not with any modes of substance.

CONCLUSION

Spinoza's fundamental insight in Book One (God, or Nature) is that Nature is an indivisible, uncaused, substantial whole—in fact; it is the only substantial whole. Outside of Nature, there is nothing, and everything that exists is a part of Nature and is brought into being by Nature. He showed these through his premises. However, the danger in Spinoza’s system, which is built on premises, is that if any premise is found to have a flaw, then, the entire system comes to nothing.

[7] S. Chukwube, Unpublished Modern Philosophy Note, Spiritan School of Philosophy Isienu. 2012

By: Nduka Anthony

LEIBNIZ AND HIS MONADS

He was born in 1646 at Leipzig, where his father Friederich was a professor of moral philosophy. At fifteen he started the study of law in the University of Leipzig and other courses such as Mathematics, philosophy, science etc. under private tutors. In 1663 he became Bachelor with a dissertation: De Pricipio Individui[1]. In the following year, he became a master of philosophy and in a couple of years, a Doctor of Law at Altdorf. Besides writing, he devoted himself further to the reform of legal procedures through the acquaintance of Friederich Von Boineburg – the latter being a former minister of the Elector of Mayence – when he went on a short stay at Frankfurt-on-the –main. From 1672-1676, he was in Paris (except a short stay in London) mainly to persuade Louis XIV of France to undertake a campaign to Egypt to divert his attention from Germany; though he was not successful. During his stay at Paris, he was opportune to meet with many Parisian scholars, one of whom was the mathematician Huygen. On his return to Germany in 1676, he lived in Hannover with Ernst August and his family and served also as court councilor and librarian.

He was born in 1646 at Leipzig, where his father Friederich was a professor of moral philosophy. At fifteen he started the study of law in the University of Leipzig and other courses such as Mathematics, philosophy, science etc. under private tutors. In 1663 he became Bachelor with a dissertation: De Pricipio Individui[1]. In the following year, he became a master of philosophy and in a couple of years, a Doctor of Law at Altdorf. Besides writing, he devoted himself further to the reform of legal procedures through the acquaintance of Friederich Von Boineburg – the latter being a former minister of the Elector of Mayence – when he went on a short stay at Frankfurt-on-the –main. From 1672-1676, he was in Paris (except a short stay in London) mainly to persuade Louis XIV of France to undertake a campaign to Egypt to divert his attention from Germany; though he was not successful. During his stay at Paris, he was opportune to meet with many Parisian scholars, one of whom was the mathematician Huygen. On his return to Germany in 1676, he lived in Hannover with Ernst August and his family and served also as court councilor and librarian.

By: Nduka Anthony

LEIBNIZ AND HIS MONADS

INTRODUCTION

There came a time in the history of modern philosophy when two contemporaries (Spinoza and Locke) reached extreme opposition and divergence – Spinoza as a rationalistic pantheist; and Locke as an empirical individualist. This notwithstanding, a twofold approximation began with Leibniz. As a rationalist, he towed the path of Spinoza and as an individualist he went with Locke.

LEIBNIZ (1646-1716)

He was born in 1646 at Leipzig, where his father Friederich was a professor of moral philosophy. At fifteen he started the study of law in the University of Leipzig and other courses such as Mathematics, philosophy, science etc. under private tutors. In 1663 he became Bachelor with a dissertation: De Pricipio Individui[1]. In the following year, he became a master of philosophy and in a couple of years, a Doctor of Law at Altdorf. Besides writing, he devoted himself further to the reform of legal procedures through the acquaintance of Friederich Von Boineburg – the latter being a former minister of the Elector of Mayence – when he went on a short stay at Frankfurt-on-the –main. From 1672-1676, he was in Paris (except a short stay in London) mainly to persuade Louis XIV of France to undertake a campaign to Egypt to divert his attention from Germany; though he was not successful. During his stay at Paris, he was opportune to meet with many Parisian scholars, one of whom was the mathematician Huygen. On his return to Germany in 1676, he lived in Hannover with Ernst August and his family and served also as court councilor and librarian.

He was born in 1646 at Leipzig, where his father Friederich was a professor of moral philosophy. At fifteen he started the study of law in the University of Leipzig and other courses such as Mathematics, philosophy, science etc. under private tutors. In 1663 he became Bachelor with a dissertation: De Pricipio Individui[1]. In the following year, he became a master of philosophy and in a couple of years, a Doctor of Law at Altdorf. Besides writing, he devoted himself further to the reform of legal procedures through the acquaintance of Friederich Von Boineburg – the latter being a former minister of the Elector of Mayence – when he went on a short stay at Frankfurt-on-the –main. From 1672-1676, he was in Paris (except a short stay in London) mainly to persuade Louis XIV of France to undertake a campaign to Egypt to divert his attention from Germany; though he was not successful. During his stay at Paris, he was opportune to meet with many Parisian scholars, one of whom was the mathematician Huygen. On his return to Germany in 1676, he lived in Hannover with Ernst August and his family and served also as court councilor and librarian.

In 1700, Leibniz helped in the founding of the society of sciences where he was the first president. He also worked on his principal work The New Essay concerning Human Understanding, which was aimed at Locke, but the publication was only possible in 1765 as a result of the death of Locke in 1704. Theodicy, another work of his (undertaken at the request of the Prussian queen) was interrupted for years due to the death of the queen in 1705. It was only possible for Leibniz to write most of his works as short essays, letters, and articles as he was enagaged in variety of pursuits which affected the development and influence of his philosophy. Leibniz was not just a philosopher, mathematician and scientist, he was deep in religion: this is evidenced in the fact that he sought for the unity of Catholicism and Protestantism. He wrote wide on the areas of his study. His thoughts range from differential calculus through monadology to Religion (The Principles of Nature and Grace) etc. Some of his works remained unpublished till after his death in the year 1716.

HIS MAIN IDEA – THE MONADS

Leibniz developed his new concept of substance, the monad, in conjunction with, yet in opposition to, the Cartesian and the atomistic principles. It was the Cartesians that made substance the main point in metaphysics, where they explained it by the concept of independence. If atoms are the smallest indivisible particles, then monads alone are the true atoms. Going further on this, he explained that every material body, no matter how small it is, can be divided, though real. Mathematical points are indivisible and unreal; but it is only the metaphysical or substantial points – soul units – alone which have the properties of indivisibility and reality. These are the monads. Added to indivisibility of the monads , is the immortality because, they cannot come into being or pass out of it in a natural way whatever, but only by creation and annihilation. The monad is not only non-spatial in character; it is self-sufficient and therefore deserves the Aristotelian name ‘entelechy[2]’.

Thus, in the monad concept are two lines of thought – Cartesianism (which he called the antechamber of true philosophy) and atomism (the preparation for the monad theory). Every monad represents all others in itself; is concentrated in all; in fact, is a miniature universe. In each individual is an infinity and a supreme intelligence. The monad is freighted with the part and bears the future in its bosom. Thus every monad, for Leibniz, is not just a minor of the universe, but a living minor which generates images of things from within without influences from without[3]. The monad has no window for inflow or outflow, but is dependent on God and itself alone.

All monads represent the universe, but each represents it differently, from its own point of view and quality. No monad represents the common universe and its individual parts just as well as the others, but either better or worse; for there are different degrees of clearness and distinctness as there are monads.

Nevertheless, certain classes may be distinguished; the boundary being between clear and obscure perceptions. In the clear perceptions can be distinguished between distinct and confused ones.[4] In the lowest level are the naked monads which pass their lives in sleep or unconsciousness. If perception rises into conscious feeling, accompanied by memory, then the monads deserve the name of soul – this is the second level. The third level lies in the soul rising to self-consciousness and to reason or know the universal truth – this is called the spirit. Each higher stage contains the lower – since the spirit can contain confused perceptions. For Leibniz, though the monads are windowless, they produce the same result as if they are constantly interacting. This he called pre-established harmony.

EVALUATION AND CONCLUSION

In the first place, I must congratulate Leibniz for a well articulated theory of substance (the monads). He presented the monads as being immortal and as being independent. In a nutshell, for Leibniz, monads are the souls of things that are. He likened the monads to the atoms in terms of indivisibility and indestructibility. Although these were obtainable of atoms in his days when a contrary opinion has not been established, Dalton’s modification of the atomic theory has made the comparison of monads and atoms irreconcilable.

Leibniz’s concept of a mechanical man – with his theory of the pre-established harmony of the monads – has presented man as a determined person (not just man, but the entire universe). This means that man is not even free to differ with others in certain acts or thinking. Even if he does, Leibniz says he has been programmed to be that way together with other men. It supposes that God has already condemned man into making particular decisions. If this is really the case, then God, who is said to be all-good, is only amusing Himself with the activities in the universe, and that man has no chance whatsoever with one who created him in His image and likeness. If this is the case, then God Himself is determined not to make man differently – that the man God made must be determined.

Leibniz has, through his works, created impacts in the history of philosophy and other areas of life. These impacts have continued to see to the integral development of man and the society. He equally challenges us to be versatile and to contribute reasonably to the growth of the universe God has created.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berkeley G., A Principle Concerning Human Understanding, London: Renascence Editions, 1999

Chkwube S., Unpublished Lecture Notes, Spiritan School of Philosophy, Isienu, Enugu State, Nigeria, 2011/2012.

D. Ruherford et al (eds.)., Leibniz: Nature and Freedom, London: Oxford University Press, 2005

Falckenberg R., History of Modern Philosophy, (London: Blackmask publishers), 2004.

Robert S, et al., Age Of German Idealism, New York: Routledge History of philosophy, 1993.

Roger A & EricW(eds.)., Modern Philosophy: An Anthology Of Primary Sources, Indianapolis: Hackett, 1998.

[1] Latin: The individual principle

[2]R. Falckenberg, History of Modern Philosophy, p.132 (Pdf version)

[3] Ibid p.133

[4] A perception is clear when it is sufficiently distinguished from others; distinct when its component parts are distinguished.

By Austyn Chimbu

EPICURUS' LETTER TO MENOECEUS: A CRITICAL OVERVIEW

By Austyn Chimbu

EPICURUS' LETTER TO MENOECEUS: A CRITICAL OVERVIEW

Introduction

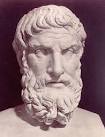

The Greek philosopher Epicurus (341 BC – 270 BC) was born in the island of Samos. By 307/6 BC, he moved to Athens where, with his friends, he established a secluded community that he called the “Garden”. He had no interest in anything that has no bearing on human conduct. His philosophy was influenced by the atomistic metaphysics of Democritus, Leucippus and the Cyrenaics. He had so many works bordering on nature, atom and void, love, problems, end-goal, Gods, holiness, and what have you.

In his letter to Menoeceus, Epicurus discussed the implications of human effort toward achieving happiness. He tries to erase fear from people’s mind, positing the idea that in order to be happy, one must have peace of mind. However, one cannot achieve this peace of mind if one is afraid of anything or anybody. Hence, he titled his letter; “How to live a Happy Life”. His letter can be critically summarized in five broad headings, viz: Exhortation, Do not fear the Gods, Do not fear death, Master you desires and live wisely.

Exposition of Text

Epicurus admonished both young and old to seek wisdom through the study of philosophy as that will help them to exercise themselves in things that bring about happiness. He urges us in this letter to Menoeceus, to believe that the gods are living beings, immortal and blessed as our common sense would make us know. However, he admonishes us not to fear the gods for they do not interfere with human affairs, contrary to the common belief that the gods give rewards and punishments to the righteous and offenders respectively.

Epicurus further presents death as nothing to terrify us about, because good and evil are experienced through sensation, but sensation ceases at death. Death and life for him cannot co-exit. He maintains that the wise person does not disapprove of life nor fear death but rather seeks to enjoy life on the basis of how well and not how long. Thus, he advocates the need to live well and to die well.

He categorizes all our desires into necessary and contingent desires. He presents the necessary desires as that which should guide our actions toward the goal of a happy life – that is freedom form pain; and once that is achieved, we possess all the pleasure we longed for. Deductively, pleasure is the absence of pain and anxiety. Hence, the criterion for judging an action as right or wrong and all our decisions as regards which is to be done or avoided are based on pleasure. The emphasis here is not on any type of pleasure, but on long-term pleasures that are characterized by peace of mind and zero pain.

Observably, the paramount aspect of Epicurus’ idea of pleasure is peace of mind. For one to achieve this, he encourages self-sufficiency as a great virtue. With peace of mind, he maintains, that one can be happy in the midst of torture. He presents ‘sober reasoning’ as that which we need to decides our everyday choices and avoidance. It will liberate us from the false beliefs which are the greatest source of anxiety.

To cap up his letter, he presents prudence as the art of practical wisdom which is more valuable than philosophy because it is the foundation of all other virtues. He maintains that it is impossible to live pleasurably without living prudently; likewise, it is impossible to live prudently without living pleasurably. He encourages us through this letter to Menoeceus to live wisely, differentiating between fate, chance and choice, knowing that what is decided by choice is not subject to any external power (fate), or randomly caused (chance).

Criticisms/Evaluation

Epicurus cannot seriously lay the claim that death is nothing to us or that he who is dying is passing through no pain, because his reasons for that are not sufficient enough. He seems to neglect the fact that some people die out of the pain that they are passing through, some beg for euthanasia while some others struggle not to die at all. Recalling the near-death experience of some people, it becomes evident that some people weep that they are about to die, some even began an unprepared confession which they would have not have made if not at the face of death. These are contrary to his view, that there is no pain in ceasing to live. I argue that there is a great pain in ceasing to live especially for one who has unresolved issues with life.

On another note, his position that we ought to behave so as to acquire happiness denies the use of human initiative and common sense, because at times, people can act in respect of certain obligation which may not even lead to pleasure at the end, but are essential for their existence. Hence, I argue that Epicurus failed to make a clear-cut distinction between the actions that will lead to this long-term pleasure and the criteria for determining such actions.

His assertion that bread and water only will confer the highest pleasure when they are brought to hungry lips implies that hunger determines whether a lip will be satisfied with bread and water or not; and the hungry lips must conform because there is no better alternative. It seems to elude Epicurus that we can forgo pleasure with what the Economists call the “forgone alternative”. If pain is the absence of pleasure, how can it then be one of the parameters of pleasure? One may subject oneself to less quality and quantity of bread (pain) so as to meet up with greater demands that will even be pleasurable when achieved.

Conclusion

From the foregoing, Epicurus’ idea of good life is that of a happy and pleasurable life which one should behave in accordance to, so as to acquire it. Expounding on how to achieve this, he assert that one ought not to live in fear of the gods, human or death. One ought to live prudently, virtuously and act wisely. The result, he said will be a pleasurable life.

By Nduka Anthony